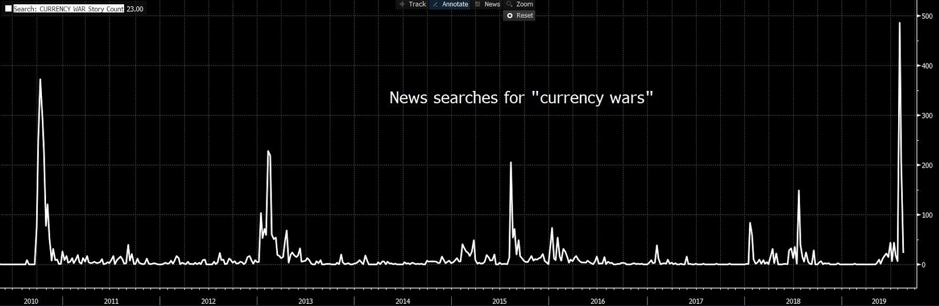

Not only have clients been ever more inquisitive about an all-out currency war, but the topic is gaining traction in the press.

"News searches for 'currency wars' have spiked recently"

What is a currency war?

The term ‘currency war’ was coined by former Brazilian finance minister Guido Mantega in 2010, highlighting his concern about overly loose US monetary policy. At the time, the US was experiencing subdued inflation, the fed funds target was a low 0 – 0.25% and the Federal Reserve was undergoing massive balance sheet expansion through quantitative easing (QE).

How does a currency war start?

A currency war occurs when multiple nations deliberately devalue their currencies in order to boost the competitiveness of its exports while importing inflation. There are many ways intervention can play out, but at its most simplistic, a government or central bank achieves this by purchasing foreign currency and selling its own in the open market.

Currency devaluation can cause extreme forex volatility and gapping risk, especially if the sell-off occurs in the less liquid ‘twilight zone’ between the US open and Asian close. The escalation of tit-for-tat trade wars, in theory, increases the probability of a currency war playing out between various G10 FX nations.

Six signs of a currency war

We thought we’d look into the indicators of an impending currency war, and lay out six key risk events and opportunities to keep an eye on when trading currencies.

- Sentiment from the Trump administration

- US dollar index (USDX on MT4/MT5)

- US dollar trade-weighted index

- USDCNH

- EURUSD

- Gold

Sentiment from the Trump administration, the US Treasury, and the Fed

The trade-weighted USD has recently hit an all-time high, with President Trump’s calls growing ever louder that the greenback is too strong against the currencies of its major trading partners, making US exports less competitive. Of course, a strong dollar means the US can import more, but that only widens the trade deficit Trump promised to end.

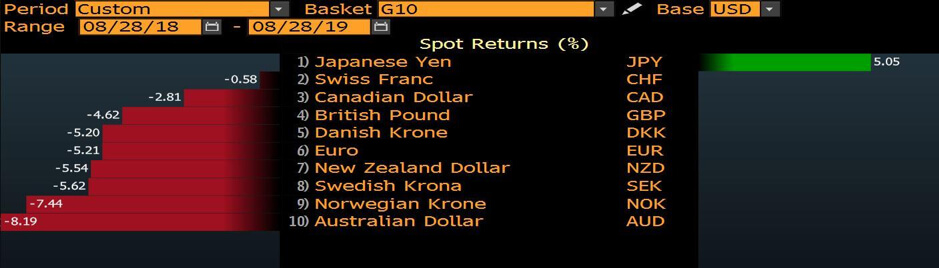

"The USD appreciated against all G10 currencies except the JPY in the 12 months to August 28, 2019."

Further, the US dollar’s role as both a domestic cyclical and countercyclical currency has driven it higher. If the rest of the world is experiencing growth, the USD tends to drop. Of course, we have seen the opposite in recent years and as global demand has tapered off and fear of recession has loomed, the US economy has looked relatively upbeat and the USD has strengthened. So, as the trade war ratchets up and global sentiment declines further, the trend has been for a stronger dollar, counter to Trump’s desire for a weaker currency.

Trump called for 100 basis points of rate cuts mid-August, accusing Powell of having a ‘horrendous lack of vision,’ and later labelling him an enemy of the United States. He was outspoken again a few days later, claiming foreign countries are taking advantage of the strong dollar and that “the Fed loves watching [US] manufacturers struggle with exports.”

Talk of intervention is ramping up. Mnuchin has signalled he would prefer currency intervention to be coordinated with the Federal Reserve and global allies, although the situation could change in the future.

So, there are no plans for currency intervention…‘for now’..

What will push the US Treasury to intervene?

US dollar index (USDX)

The US dollar index (USDX/DXY) is a measure of the USD against a basket of six foreign currencies: the euro, Japanese yen, British pound, Canadian dollar, Swedish krona, and the Swiss franc. The index increases as the USD strengthens and declines as the USD weakens. In the chart below you’ll see the USDX has been steadily increasing since April 2018, where the price is currently hovering just above the 98-handle and the top of its trading range. One suspects that if we saw a break of 100, and calls of a test of the 2017 high 103, it could heighten the chance of intervention.

Remember that devaluing a currency is a drastic measure. What’s important here isn’t just the levels to watch, but the rate of change in price. The faster the pace of change, the greater the prospect of intervention.

Listen to sentiment from Trump and his administration. Even if plans are currently off the table, the more noise Trump makes wanting to devalue the dollar, the more the markets will price in the possibility.

The trade-weighted USD

The trade-weighted USD index determines the purchasing power of the greenback, similarly measured against a basket of foreign currencies. It’s measured against 26 currencies, often called the broad USD index due to its wider measure than the USDX.

Here, we see the index at an all-time high and starting to trend. One suspects if we saw the index 3-5% higher then calls for intervention will increase. One to watch.

USDCNH

The United States formally labelled China a ‘currency manipulator’ in early August, with trade hawks arguing Beijing has kept the yuan low for years in order to boost exports. The tension has built up since.

The onshore yuan (CNY) doesn’t float freely. The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) manages the market value, by setting a point within 2% of the trading day’s midpoint rate. While few would argue the PBoC hasn’t previously influenced its currency, the yuan is expected to decline every time more tariffs are levied on Chinese imports to the US. In fact, despite the PBoC arguing that a stable currency is advantageous, we could see the CNY decline at a faster rate than it currently is to counter the escalating trade war.

Trump urged the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to get involved upon branding Beijing a currency manipulator. However, the yuan’s movement did not meet the IMF’s checklist for currency manipulation.

Nonetheless, the US Treasury is playing Trump’s game. The chart below shows a sharp rally in early August, to the 7.00 level in USDCNH, upon announcement of an additional tariff on Chinese imports. Mnuchin responded saying ‘China has taken concrete steps to devalue its currency.

"USDCNH \u2013 the off-shore yuan has weakened against the USD"

The PBoC has signalled it could weaponise its currency, although this would potentially be counter-intuitive as it may just incentivise capital outflows from China, which would act as a tightening of financial conditions. However, it seems clear if trade tensions continue to escalate, CNH is likely to drop further against USD.

The rhetoric has started. The US has branded China a currency manipulator, and Trump has laid the groundwork for a potential retaliatory USD devaluation.

EURUSD

Trump has also lashed out at The European Central Bank (ECB) for extreme monetary policy stimulus that’s driven the EUR lower against the greenback. He’s claimed an unfair advantage for European over US exporters.

"The euro has been steadily weakening against the greenback since early 2018"

The ECB is currently commanding a -0.4% interest rate. Further easing to -0.5% will likely be seen in its 12 September meeting, amid Germany showing signs of recession. The more the ECB eases, the closer US Treasury might get to its tipping point for currency intervention.

How would it happen?

If the US Treasury pursued a dollar devaluation, farmers and manufacturers would get a boost from more competitive exports. At the same time, the US will pay a higher price for imports, which could have a positive inflationary effect, although also acting as a handbrake on consumption.

With dampening global growth and an unprecedented strong dollar, you can understand why Trump is championing a weaker USD and why fears of as currency war are mounting.

But as US exports become more competitive, the rest of the world’s exports face a disadvantage. In uncertain economic times, foreign economies would be quick to fight back to remain competitive. Global interest rates are at record lows and in some cases negative, which grants little room to ease through rate cuts. Nations might see no option but to devalue their own countries in retaliation. At least, that’s the way the market will see it.

We then look closely at the Bank of Japan (BoJ) here, which has a history of forex intervention. The central bank, at the helm of the world’s third-largest economy, last intervened in October 2011, bringing the JPY down from a record high against the dollar. Yet several other attempts by the BoJ to devalue the JPY saw ever-diminishing returns. Even if the BoJ wished to devalue the yen amid a currency war, it would need to question whether a sell-off would work as desired.

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has held a consistent line that a weaker AUD would be advantageous, as have the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ). “If the world interest rate changes, we have to change ours too,” RBA Governor Phillip Lowe said at the Jackson Hole symposium in Wyoming late August. The RBA cash rate is currently a record low 1%. So USD intervention, at a time of economic fragility in these economies, would have traders cautious of unconventional policy here.

The eurozone has pursued aggressive monetary expansion in recent years to pick up their stagnating economies and it hasn’t worked. Clearly a stronger EUR would not be welcomed, but with the ECB likely to go hard in the 12 September meeting, one questions what they would have to fight a US Treasury selling USDs.

We look to gold as an investment here. So, what wins? Investors will turn to gold as a safe store of value, not that they need a reason to buy it. As investors become more nervous that a currency war could break out, the higher gold should go. The precious metal could rally and trade as its own currency.

Emerging markets will also likely see considerable gains should the US pursue a weaker dollar.

The fact is intervention is on the radar. We’ve looked at the triggers in a world fearing recession, and really, if we are to see a currency war, it will be driven by the US. We watch and wait, knowing that if it comes to fruition, the forex markets will come alive with volatility.

做好交易准备了吗?

只需少量入金便可随时开始交易。我们简单的申请流程仅需几分钟便可完成申请。

此处提供的材料并未按照旨在促进投资研究独立性的法律要求准备,因此被视为市场沟通之用途。虽然在传播投资研究之前不受任何禁止交易的限制,但我们不会在将其提供给我们的客户之前寻求利用任何优势。

Pepperstone 并不表示此处提供的材料是准确、最新或完整的,因此不应依赖于此。该信息,无论是否来自第三方,都不应被视为推荐;或买卖要约;或征求购买或出售任何证券、金融产品或工具的要约;或参与任何特定的交易策略。它没有考虑读者的财务状况或投资目标。我们建议此内容的任何读者寻求自己的建议。未经 Pepperstone 批准,不得复制或重新分发此信息。