分析

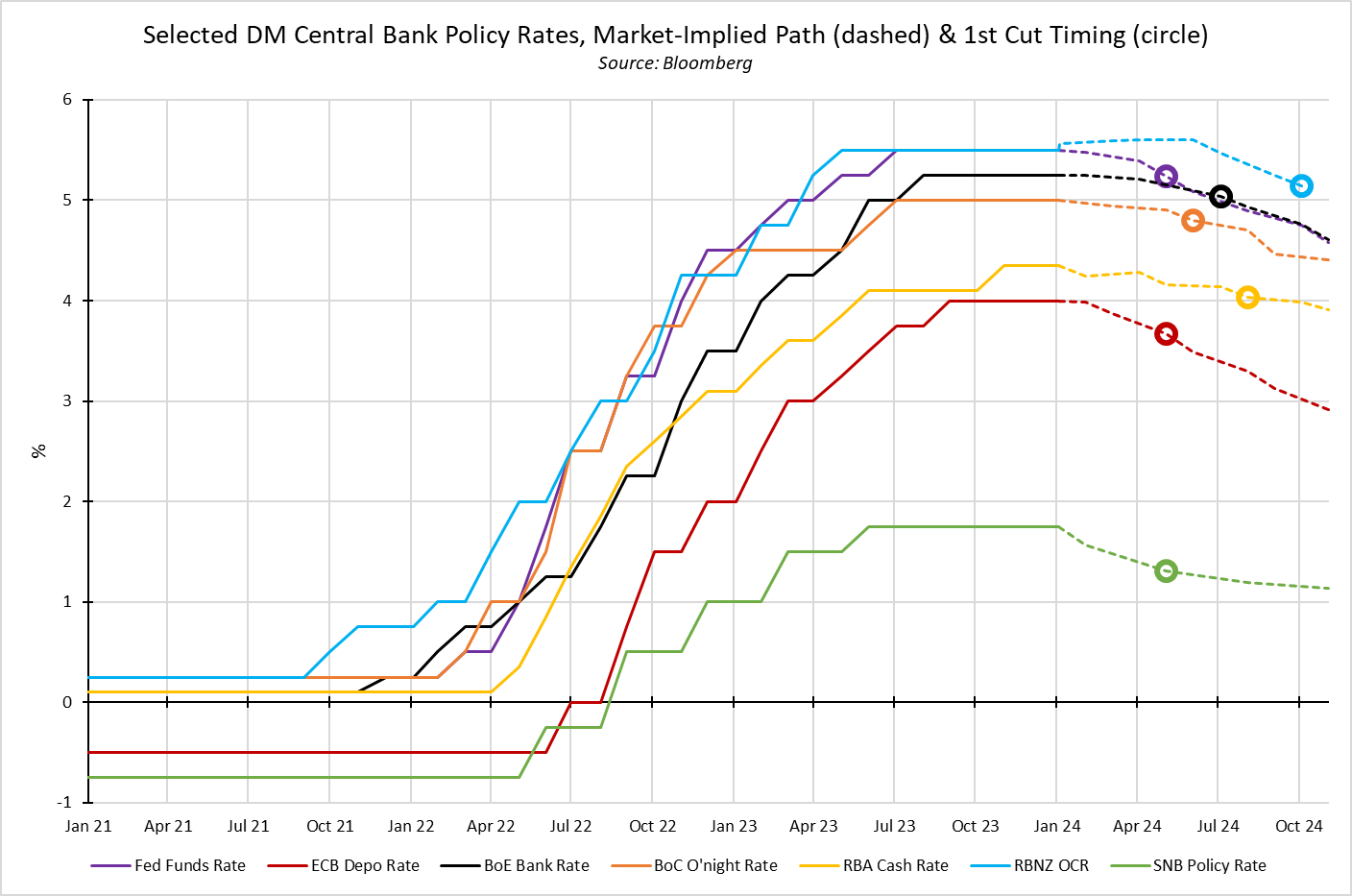

Even after a hotter-than-expected January US CPI report, money markets continue to price a ‘summer of rate cuts’. Though the, somewhat futile, game of guessing, and second-guessing, when central banks will kickstart easing cycles, and how deep these cycles will be, continues on a daily basis, consensus is rapidly forming around a single view – that most DM central banks will deliver the first 25bp cut somewhere between June and September, and that cuts will probably continue until around the middle of next year.

I think there are a number of important things to note regarding this.

Firstly, we should consider what may force a rate cut sooner than the halfway mark of the year. For most, particularly the FOMC, such a catalyst would most likely have to be some kind of financial accident – regional banks becoming an issue once more, CRE strains making themselves more known, or a ‘black swan’ that we cannot as yet foresee. In any case, this leads to the logical conclusion that if a cut were to come before June, it would likely be one much greater than your ‘common or garden’ 25bp rate reduction, as any such financial stability issues would be near-certain to result in much more forceful policy action.

I would set both the ECB, and the SNB, aside from this view, however, owing to rapid disinflation being seen in both economies, with Swiss inflation now in the low-1%s, and as the eurozone economy continues to rapidly lose momentum. April, and March, respectively, seem the most likely timelines for cuts from each.

Secondly, is the synchronised nature of the easing cycle that markets price. Just as G10 central banks rapidly raised rates in line with each other in 2022-23 to stamp down on what had been misleadingly labelled ‘transitory’ inflation, policy rates are seen falling at a similarly synchronised pace. While there will, naturally, and as touched on, be some minor variation in timing and magnitude, the base case is that most G10 central banks will ease somewhere around 100bp this year, with a similar degree of easing likely the following year, taking rates – roughly – back to a more neutral setting, particularly if, and when, inflation returns back to the 2% target.

This synchronicity, coupled with the increased liquidity that policy loosening will provide, should help to keep something of a lid on volatility, particularly in the equity, and fixed income space, as we approach election season in the US, and likely the UK, later in the year. Furthermore, the end of quantitative tightening, perhaps an underdiscussed topic at this stage, will likely provide a further fillip to global equities, though US outperformance seems set to continue.

Such a synchronised easing cycle does beg the question, however, of whether some – or even, most – DM central banks are now simply in a waiting game, wanting the Fed to be the first to cut, before kicking-off their own easing cycles. As noted, some, like the ECB and SNB, are unlikely to be able to play such a waiting game, though others, such as the BoE and RBA, will likely hold out as long as possible, as inflation proves somewhat stickier. Of course, the BoJ remain an outlier here, though the 10-20bp of tightening that Japan seems likely to deliver this year seems unlikely to significantly move the needle.

Hence, while this relatively co-ordinated easing cycle is likely to dampen vol more broadly, tradeable themes are likely to be relatively plentiful in the G10 FX space. A broad-based long USD as the ‘exceptionalism’ narrative shows little sign of slowing feels just, with long USD/CHF and short EUR/USD two particularly attractive options given the aforementioned idiosyncratic factors impacting both economies, while the GBP may – at long last – outperform if, indeed, the ‘Old Lady’ does maintain Bank Rate at 5.25% for longer than peers, as seems likely given continued sticky services inflation.

Nevertheless, the broader framing of this entire policy easing debate must be that the defining feature of almost all central bank rhetoric over the last few months has been aimed at engineering as much of one thing as possible – flexibility. All the talk of data-dependence, seeking more ‘confidence’ of inflation’s return to target, and refusing to give any calendar-based guidance as to the timing of cuts, has been a deliberate effort from policymakers to give themselves as much optionality as possible.

In short, central banks can now reasonably cut whenever they desire, and whenever they need to. While markets price a consensus that should result in relatively low volatility, and a relatively gradual cycle of policy loosening, if the last few years have taught us anything, it should be that markets rarely follow such a linear path.

That central banks can, at any point, unleash a liquidity bazooka dependent on prevailing economic and financial conditions, should provide the necessary reassurance to keep a lid on vol, and to keep the medium-run path of least resistance leading higher for risk-sensitive assets.

Related articles

此處提供的材料並未按照旨在促進投資研究獨立性的法律要求準備,因此被視為市場溝通之用途。雖然在傳播投資研究之前不受任何禁止交易的限製,但我們不會在將其提供給我們的客戶之前尋求利用任何優勢。

Pepperstone 並不表示此處提供的材料是準確、最新或完整的,因此不應依賴於此。該信息,無論是否來自第三方,都不應被視為推薦;或買賣要約;或征求購買或出售任何證券、金融產品或工具的要約;或參與任何特定的交易策略。它沒有考慮讀者的財務狀況或投資目標。我們建議此內容的任何讀者尋求自己的建議。未經 Pepperstone 批準,不得復製或重新分發此信息。