The ‘summer of easing’ is something discussed at length recently in these pages, though in the central banking world summer appears to have arrived early, with the Swiss National Bank (SNB) having become the first G10 central bank to deliver a rate cut this cycle at their March meeting, as domestic inflation settles towards the bottom of the SNB’s target range.

Nevertheless, although the SNB may have won the ‘race’ to deliver the first cut, other G10 central banks remain highly likely to follow in relatively short order.

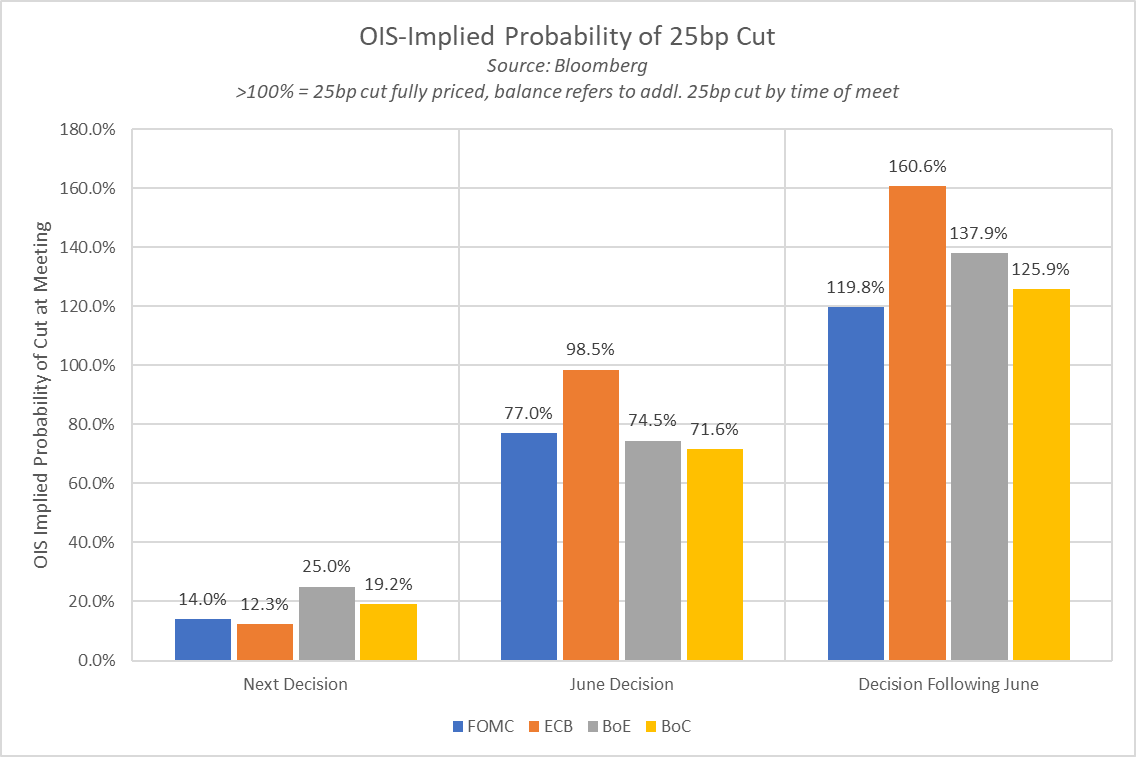

The ECB, for instance, have all but pre-committed to a rate cut in June, despite retaining a data-dependent pretence; the BoE seem likely to cut in June, with Governor Bailey having noted that rate cuts are now “in play” at future meetings; while the FOMC are also likely to kick-off the easing cycle in early-summer, having appeared somewhat desperate to begin policy normalisation last week, with the latest SEP pointing to unchanged rate expectations (75bp cuts this year), despite an upwardly revised inflation outlook.

As discussed previously, with the policy backdrop set to become increasingly supportive, equity volatility should remain relatively limited.

This is not to say that there are no risks present – clearly, there are, both from a geopolitical standpoint, and an economic one, particularly as services inflation remains sticky. Instead, it is to say that looser monetary policy (via both rate cuts and an end to quantitative tightening) should, to a significant degree, work to insulate risk assets from significant adverse shocks.

Furthermore, one must recall the central bank put that is once more in place, with inflation back at, or within touching distance of, the 2% target in most DM economies. This means that, if such an adverse shock were to eventuate, policymakers possess the ability to cut significantly, and deliver liquidity injections if necessary, to further insulate both the economy and markets.

In short, while dips, or even deeper pullbacks, cannot be ruled out, and would in fact be healthy to remove potential froth from the market, they should remain short-lived, and relatively shallow in nature. Hence, the path of least resistance for the broader market should continue to lead to the upside, with vol subdued.

The same, however, cannot be said for the FX market. Some signs of renewed life have already begun to emerge, with JPM’s G7 FX vol index spiking to a 6-week high – though, it must be said, much of this move was driven by higher JPY vol over the BoJ, and has since subsided.

This may, however, prove to be a small taste of things to come as the ‘summer of easing’ progresses.

While the direction of travel for all G10 central banks, bar the BoJ (whose 10bp hike is insignificant), is one towards easier policy, and rates moving back to their neutral level, said policy normalisation will take place at differing speeds, and to differing magnitudes, opening natural policy divergences for traders to take advantage of.

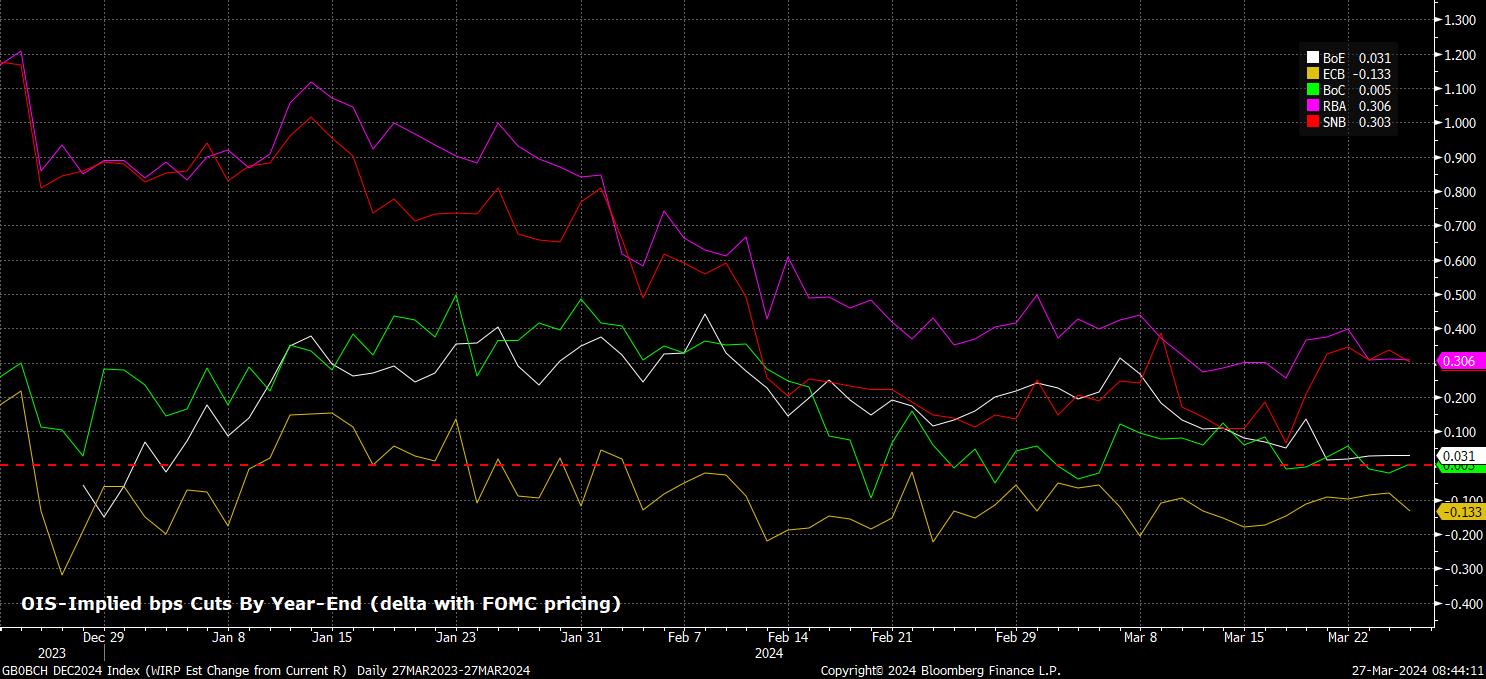

Comparing the market-implied pace of easing for various G10 central banks to that implied for the FOMC helps to illustrate that point; though, interestingly, OIS currently implies that only the ECB, and the BoC, will ease to a greater degree than Powell & Co. over the remainder of 2024.

This pricing, however, should not be taken as gospel alone.

One must also consider the direction in which risks to the policy path tilt. On this note, one would argue that for the FOMC, risks to the market-implied path are biased in a more hawkish direction, with services inflation remaining sticky, CPI continuing to print hotter-than-expected, and with just one FOMC member now pinning their ‘dot’ below the median expectation, compared to five last time around.

In contrast, elsewhere, risks appear biased in a substantially more dovish direction. This is especially true of the ECB where, although the first cut remains likely to be delivered in line with that of the FOMC in June, dovish overtures from Governing Council members are growing increasingly loud. The same can be said of G10 central banks elsewhere – fragile domestic property sectors raise dovish risks for the BoC and RBNZ, along with the BoE, while the Riksbank have already flagged that it is “likely” a cut can be delivered as soon as May if the inflation outlook remains favourable.

Logically, one would therefore expect yield spreads to move back in the greenback’s favour as the ‘summer of easing’ gets underway, helping to support the next leg higher in the dollar’s recent run, as the FOMC become something of a hawkish outlier among G10 peers. While the USD and equities rallying together is unusual, such a scenario remains the base case for now.

Related articles

此處提供的材料並未按照旨在促進投資研究獨立性的法律要求準備,因此被視為市場溝通之用途。雖然在傳播投資研究之前不受任何禁止交易的限製,但我們不會在將其提供給我們的客戶之前尋求利用任何優勢。

Pepperstone 並不表示此處提供的材料是準確、最新或完整的,因此不應依賴於此。該信息,無論是否來自第三方,都不應被視為推薦;或買賣要約;或征求購買或出售任何證券、金融產品或工具的要約;或參與任何特定的交易策略。它沒有考慮讀者的財務狀況或投資目標。我們建議此內容的任何讀者尋求自己的建議。未經 Pepperstone 批準,不得復製或重新分發此信息。