分析

Macro Trader: The First Cut Is Always A Few Months Away

The ‘carrot and stick’ approach is one which stems, originally, from the way in which a rider used to encourage a donkey to move forward by dangling a carrot in front of its face. If the donkey wouldn’t move, it would be hit with the stick.

This analogy could well be used to describe the market’s current relationship with the Fed. Risk assets are rallying, as Powell & Co dangle in front of them the prospect of rate cuts, and an end to quantitative tightening. However, if inflation were to remain sticky, or make a significant resurgence, markets would be hit with the big stick of more hawkish rhetoric, or rates remaining higher for longer.

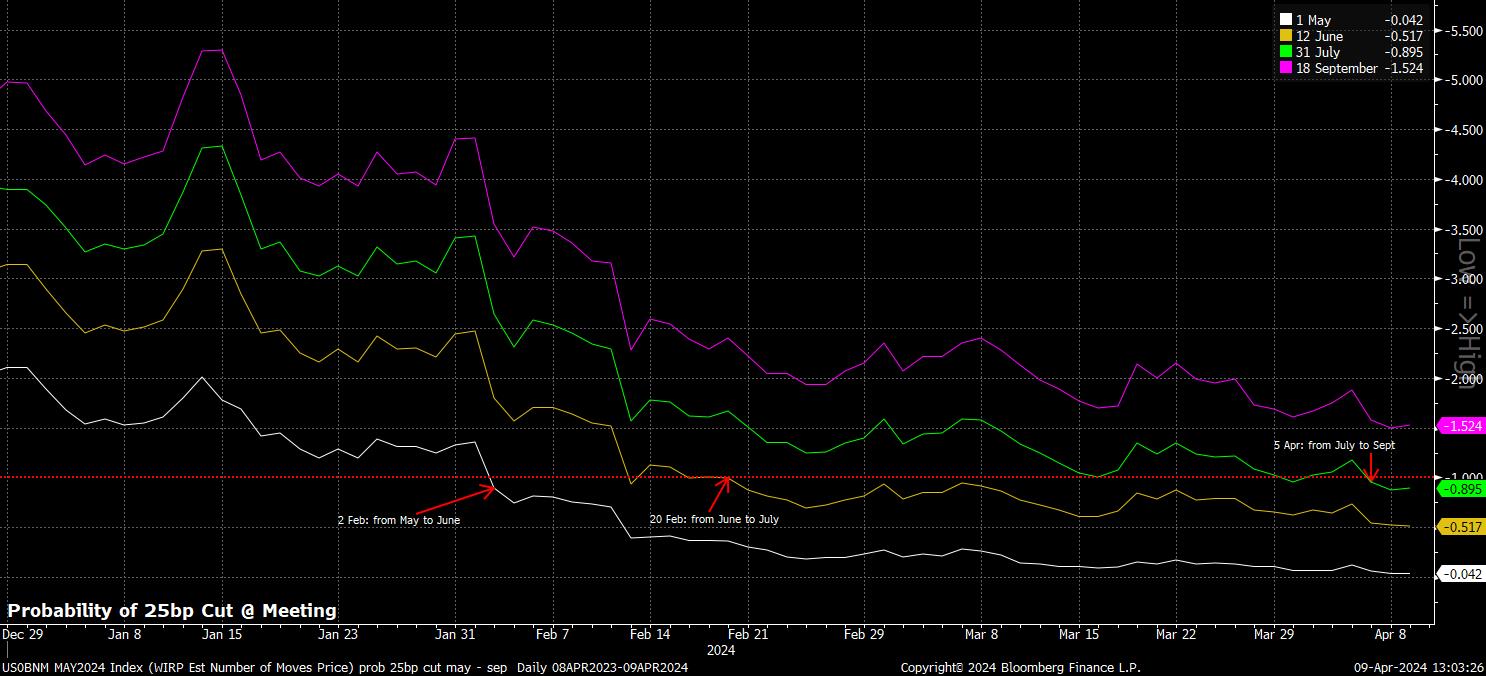

If that analogy is too contrived, perhaps a chart will better illustrate this point.

It feels as if, for most of the year thus far, the first 25bp rate cut has always been three or four months away. In January, pricing shifted from May to June; in February, from June to July; and now, in early-April, from July to September. Some market prognosticators are now even questioning why the Fed would even need to cut at all this year, given the continued tight labour market, and stubbornly high services inflation.

The continued pushing back of rate cut expectations does, naturally, beg the question of what the market implications of such a shift may be.

Answering this question depends almost entirely on what one views as the main driver of the risk rally seen this year, with the S&P trading just under 10% higher YTD, having already notched 22 record closing highs.

Some may argue that the rally has been constructed on bets that the Fed will cut rates this year. It is, however, tough to argue that this is the case, given that the S&P’s rally has come not only as the OIS curve priced out over half of the 160bp of cuts priced in at the start of the year, but also given how the market has continued to rally in spite of an aggressive sell-off at the front-end of the Treasury curve, with benchmark 2s now yielding the most since last November.

_spx_v_2024-04-09_13-03-06.jpg)

Instead, a much more plausible, rational, and believable explanation is that the rally has been built on what the Fed could do, if they so desired, or saw the need to.

Clearly, this is a rather more nuanced view of the FOMC outlook. Rather than focusing on whether Powell & Co will deliver the first cut in June, July, or even later; rather than debating how much the FOMC will cut this year, or next; what matter is that, if the Committee wanted to, with inflation on its way back – albeit bumpily – to the 2% target, it can cut rates, perhaps significantly, and can deliver fresh liquidity to the parts of the economy where it may be required.

In short, even if pricing of the first cut continues to be pushed back, the ‘Fed put’ remains in place, giving participants confidence to increase risk exposure, or at the very least remain expose, knowing that policymakers have their backs once more.

This should, in turn, keep the path of least resistance leading to the upside for equities, naturally with a US bias continuing to be favoured, while also keeping any dips relatively short-lived, and shallow. At the same time, vol is likely to remain subdued over the medium-term, barring knee-jerk spikes over key risk events, such as CPI (10th April) and earnings reports, with Q1 reporting season kicking off on 12th April.

The FX market, in contrast, is likely to be a little more interesting, given the divergence that should play out between the FOMC, and G10 peers.

While risks to the FOMC outlook tilt in an increasingly hawkish direction, risks to central bank outlooks elsewhere are pointing in an increasingly dovish one, as the below chart illustrates.

There are very sound reasons for this.

The ECB have, effectively, already pre-committed to delivering the first cut in June, noting that they will know “a lot more” by then, particularly in terms of eurozone earnings growth, and with CPI on track to tag the 2% target later this year.

Similarly, the BoE are likely to achieve the 2% inflation target in the spring, albeit briefly, while earnings growth is also beginning to moderate; furthermore, with the MPC also flagging that policy will remain restrictive even if cuts are delivered, an early-summer Bank Rate cut is starting to look increasingly likely.

In Canada, meanwhile, the rather disastrous March labour market report has increased the risks of a dovish BoC pivot this week, and a subsequent cut at the next meeting, with unemployment at its highest since January 2022, and the economy having unexpectedly shed 2.2k jobs last month. Headline YoY CPI, at 2.8% in February, is also back inside the BoC’s target band, and on a steady downward trend.

Lastly, the SNB, who became the first G10 central bank to begin policy normalisation with a 25bp cut last month, look set to continue to ease, as inflation remains rooted to the bottom of the target range, and with policymakers likely seeking to keep pace with the ECB’s easing cycle, in order to avoid any significant strengthening of the CHF.

Putting all this together, and adding in likely late-summer cuts from the RBA and RBNZ as well, it seems plausible that the dollar’s strength should continue. This is especially true if the ‘US exceptionalism’ narrative continues to run as strong as it is at present, with US data consistently surprising to the upside of consensus expectations, as the outlook dims elsewhere in DM.

Related articles

此處提供的材料並未按照旨在促進投資研究獨立性的法律要求準備,因此被視為市場溝通之用途。雖然在傳播投資研究之前不受任何禁止交易的限製,但我們不會在將其提供給我們的客戶之前尋求利用任何優勢。

Pepperstone 並不表示此處提供的材料是準確、最新或完整的,因此不應依賴於此。該信息,無論是否來自第三方,都不應被視為推薦;或買賣要約;或征求購買或出售任何證券、金融產品或工具的要約;或參與任何特定的交易策略。它沒有考慮讀者的財務狀況或投資目標。我們建議此內容的任何讀者尋求自己的建議。未經 Pepperstone 批準,不得復製或重新分發此信息。

.jpg?height=420)